Delays arranged:

< Bettina Buck invites John Reardon >

Listen to that. It sounds so beautifully screwed-up on purpose.

Two or three years ago Bettina Buck told me that she was thinking of working on a book that would collect all four episodes of her series of invitations, and mark the end of the project. We discussed the book on several occasions: would it document the shows? Or, given the fragmentary and partial documentation, would she invite the same artists to contribute with something specific for the publication? Would the book instead represent another episode altogether? Which texts would it include, and which kind of narrative should recount this project that has seen her duet with a number of artists whose practice she felt close to, and curious about, to the point of opening up an invitation to a solo show, as a way to reassess her own practice – and vice versa – through a close proximity with, in order of apparition: Sara Barker, Peggy Franck, Marie Lund and Laure Prouvost?

Then, the book was somehow forgotten. Instead, the invitation to write this fifth episode, as I did for the first and the third already, arrived. With John Reardon, this time. One would assume that the condition that makes this series possible – sharing time, sharing space – is reflected in the writing that accompanies the project. Not quite. I didn’t know Sara Barker, but her being in a residency in Rome, where I live, made possible to meet and discuss her work. For the third invitation of the series to Marie Lund, I knew well the practice of both artists, however they decided that I could – actually should – write blindfolded. They told me that the show would be called Motor, and that was all for a long time, until they had pity on me and disclosed the list of works. (Incidentally, I loved the title – and it did ignite some thinking. They were right).

I received some pictures from Bettina and John working on the show a few days ago. I look at a picture of John laying on the floor, applying white tiles on a sheet of latex and smiling, and one of Bettina standing in the gallery space with a maniac killer look – and I think: I should be there. Reality check: I am in Rome, miles away, trying to make sense of the material that I received in three separate emails: pictures of the gallery. Images and list of works. Snapshots of these days of preparation, and collaboration and condivision. The picture of a plant that might be potted in a partially glazed vase, to be placed on a tiled portion of canvas positioned on a windowsill and hanging from the wall, which was sent as a reply to my sms asking after the material of another work on show. The show opens tomorrow, where is my text. While fighting my sense of guilt having dis-attended the engagement that I maintain is essential in writing, I started thinking that the invitation to partake in the duet as voice, foresees or is able to include failures, errors, imperfections. That there is space, in other words, for a kind of writing that can overcome an imperfect engagement with a leap of curiosity, and that perhaps is able to contemplate its own fragilities and failures. I think this is the reason for having me, yet again – despite my limits, and distance. I think that Bettina invites me in part, because of my long and ongoing conversation with her work. In part, because she likes to play with me – it can work, or not: and this does indeed reflect the structure of her project. So, let’s play.

A few things I want to say about this fifth chapter.

The series Bettina Buck Invites plays on two tables. One is the curatorial strategy of pairing up two practices as a way to illuminate aspects that otherwise would be overlooked, as two objects one next to the other amount to much more than the sum of its parts. The other is the special kind of dialogue that exists between artists, that enriches one another’s practice, that intimacy given by sharing a studio for example, and that leads to a lifetime commitment with the ideas of someone whose practice can differ in most aspects but substantially shares a similar attitude towards, well, life. The project recreates for a limited time that unconditional dialogue that allows for contradictions and misunderstandings as well as common and shared interest. We – the audience – are not allowed to penetrate this space, it is a playground constructed by the artist to explore the work and the attitude of another artist: a space stretched to accommodate two individuals that not necessarily worked together or have known each other for a long time. Also, it interprets the exhibition as a generative space, a space of uncertainties and negotiation, that radically differs from the assertive position of the solo show or the solitary, secret and protected time in the studio. It could lead to a total failure, or produce sparks.

“Why would an artist demur at the prospect of a finished work, court self-sabotaging strategies, sign his or her name to a painting that looks, from some perspectives, like an utter failure?” – asked himself Raphael Rubinstein in an article from 2009 that reads in the history of modern art a foundational skepticism, “we see it in Cézanne’s infinite, agonized adjustments of Mont St. Victoire, in Dada’s noisy denunciations (typified by Picabia’s blasphemous Portrait of Cézanne), in Giacometti’s endless obliterations and restartings of his painted portraits, in Sigmar Polke’s gloriously dumb compositions of the 1960s. Something similar can be found in other art forms, in Paul Valéry’s insistence that a poem is “never finished, only abandoned,” in Artaud’s call for “no more masterpieces,” and in punk’s knowing embrace of the amateurish and fucked-up. The history of modernism is full of strategies of refusal and acts of negation”.

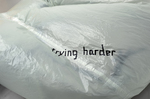

Unfinished, imperfect, unstable, collapsing are terms that both Bettina Buck and John Reardon explore, evoking the possibility of failure as constructive part of the work, a type of action that is not privative neither negative, but generative. Untitled (Trying harder), 2017 is a plastic form inflated (but never fully) and deflated (but never entirely) by a blower making a loud noise, positioned in the gallery. The title of the work is written with black gaffer tape on the sculpture, as if it would be a comment rather than a title, or an exhortation. This work by John Reardon reminded me of an older piece by Bettina, also occupying an eccentric position in the exhibition space: Falling Galley Surface (in Plastic) (2011), a roll of transparent plastic representing the entire surface of the exhibition space, hidden between the beams of a ceiling, that would eventually unravel over time – a piece that seems to dialogue with Reardon’s intervention perhaps more directly (too directly?) than Untitled (300 tiles), 2017 and Domestic device, 2017 shown here. All these works exist in the attempt to maintain form and anti-form in balance and declare a performative attitude that is characteristic of her practice. But through the proximity with Reardon’s work, another aspect of her work emerges, one that I realized I have always overlooked in Bettina Buck’s work: there is a great deal of irony in the efforts that these works have to make to maintain a shape. There is humour.

Liminality is a position that Bettina Buck’s works often occupy. Works hide behind walls, they are squashed in the ceiling, they collapse and mimic a tiled floor, you step on them as you climb a short staircase – in order to detect them, you are forced to apprehend the context in which they are exhibited, to question the space and the conditions of their appearance. Similarly, Action to produce a high degree of uncertainty (2017) traces the conversation that John Reardon had with the residents of the apartment block about the gallery opposite and about what art can be: for the time of the exhibition they will attach a single plastic bag to their balcony. The piece, reminded me of Home Run, an action conducted by Gabriel Orozco in occasion of his first solo show at MoMa in 1993, when he installed on the windowsills of the office building facing the museum’s courtyard, an orange in a teacup. In the case of the Mexican artist, the action translated one of his minimal interventions in the everyday, events constructed with minimal means to become photographs.

Reardon’s action is also documented inside the gallery with the two pictures in the gallery seen from the apartment block and of the apartment block as seen from the gallery, but the image here documents a tautology, and rather than interrogating the possibility to contaminate the real, it addresses the role and the relationship between art spaces and urban fabric – art crowd and inhabitants of the neighbourhood, but made humble by the object that marks such exchange. Volatile, as a plastic bag in the weather of a Berlin winter. This is a reoccurring preoccupation in Reardon’s work, addressed in works such as– for example – Billboard (2011) – a text that while taking a large portion of space is only visible from one room, or in his incursions in the pages of Art Monthly with a series of limited edition Posters (2007). Or again – and again with a different approach – in his Disappearing Mural (2000), a wall drawing on the entire surface of an apartment block that was painted in a wet-look varnish which rendered it invisible for most of the time as it rains almost every day where its located.

Also Bettina Buck’s Found object, 2017 seems to address, interrogate and lead to yet another ‘space’ for us, the audience, to consider as constructive of an exhibition: that of the production of work, the storage, the workshop. This sculpture is composed of a pallet, on which a halved stone is resting, its two parts - separated as if they should be completed - on four packets of clay. A proposition for a work, perhaps. A resting piece. An invitation to complete it.

(Titles are important for Bettina. They point you in a certain direction, they allude to the functioning of the work (or to the actions they could potentially undertake), they comment, and sometimes they define the personality of some pieces. The same happens with the subtitles of these series of invitation projects: Solid objects. Motor. All my mistakes I made for you. Delays arranged.

They define Buck’s practice between sculpture and performance, gravity and movement).

If I would have put together Buck and Reardon in a show, I would most probably have insisted on presenting

Relic – a work of which the two artists share the birth, and own two different versions of.

Relic, 2007, by John Reardon, is one of the two images printed in 4000 copies for the Poster series: the photograph of a hand – that could be a museum artefact – in the gesture of blessing, distributed with an issue of Art Monthly as a viaticum, or talisman, for the art community. The hand, one notices a moment later, has six fingers. Relic, 2011 by Bettina Buck, is a bronze sculpture representing a hand – that could be a museum artefact – from which two fingers are missing. The hand, one notices a moment later, originally had six fingers.

The hand was sculpted by Bettina for John, and initially was meant to be just a prop for the photograph. But when it missed the fingers, it became interesting enough to Buck to become a work in itself, translated this time into bronze.

In one case, we have an object made into an image circulation and distribution, in the other a prop cast in the most traditional material that defines sculpture. Both point at the system of beliefs that make the apprehension of an artwork possible.

And here is the inevitable distance from curatorial practice and the sharing of time, and space, and gestures, and conversations that the two artists have shared in the past years, that makes it useless the showing of this piece – because there is so much more than that that could be experimented with through Delays Arranged. More attempts, more ideas, more failures, more risks, more utopias. And sparks.

Cecilia Canziani

The conductor couldn’t fool me today, all prepared and awake. Soft chair and my resting body, a vessel downstream now, as I cuddle with the warmth of my blood.

“The world here and now does exist.” I turned my relaxing neck to locate the conductor once again, obviously not settled by a valid ticket. I put out the burning books in front of me, excused myself for the behaviour, and gazed out the foggy morning window again, as a profound sensation of size enrolled.

“Mind you” she continued, “I’m not talking about any out-of-this-world science-fiction type parallel universe, I never would. I’m talking about this chair right here, and your resting body.”

A breath too short, two lungs too shallow. I’m trying harder now, but to pull away from the world I knew? A profound silence fell over us. I took a slug of the whiskey, all words were said for now.

When I was alone again, I went over the story piece by piece. It didn’t lead anywhere. It is for many natural to assume that a material object’s mass is an intrinsic property of the object, which it possesses independently of any relation which it may bear to any other object. This was Newton’s assumption, and, certainly, seems to have turned on Calypso in the aisle as well. But if I am correct, it seems like the assumption is fundamentally mistaken and mass turns out to be a relational property which objects can possess only in virtue of being parts of a complex dynamical system, I thought, as the station reached out from the void, and entered into my view.

“It’s all a matter of cognition.” She was still there, but slightly melted now, dripping almost on me. “The world is perceived” she continued, “and that’s what’s changing is in your brain.”

I might not be strict in the physical sense, but I have limits to my love.

I am no Odysseus, when I close my eyes, my blood no Ogygia, when my shadow admires the sky, and she must know. The cloudy mirror sends me back to a chair, to my vessel in the stream.

Rasmus Kjelsrud

snookered

Recently, Hagen introduced me to the upcoming exhibition - Delays arranged: Bettina Buck invites John Reardon - at Åplus.

He enthusiastically told me about Bettina Buck‘s latex tiled objects that would decay over time, guaranteeing the replacement of the broken one with a brand new one. From John Reardon he knew of an action in which Hans Ulrich Obrist and Richard Wentworth were invited by the artist for a bus ride to conduct a conversation with them. The bus driver had been instructed to drive into a traffic jam. When Mr. Obrist became impatient after some time, Reardon pointed to the awkward traffic situation, he was trapped. The conversation now took much longer than the participants had expected.

Pretty naughty, I thought to myself, wondering if I thought it was good or even necessary. However, I had to think of Ringo Starr, who only allowed the weekly newspaper Die Zeit ten minutes for an interview. But it is well known that gods already say enough to say great things. Later I realized a comparison with Snooker, because who is snookered, is in an awkward position. The sports reporter likes to translate that or something similar. Here, however, I find the original more fitting, as a snooker was the lowest rank in the civilian military in India.

And whenever the officers played billiards with each other, they tried to put their opponent in an awkward situation, thereby demoting him to a „snooker“. So it‘s a kind of grounding, a retrieval to Mother Earth, and that‘s not going to be completely wrong here.

Bettina Buck does not kill anyone, she plays with open cards. The work pleases, is bought, falls into disrepair and returns after being exchanged like a phoenix from the ashes.

So far so good, and that some contemporary art must be restored after a short time, is not new, one can confidently speak of an art restoration industry. Thus, artist U constantly tours his collectors to freshen up his paintings, and artist A‘s brother has until his retirement to restore his works worldwide.

If U is convinced that only freshly powdered colors are really radical, and if it is A‘s technical inability that his work ages so quickly, Bettina Buck sees the decay of her work as part of her own artistic program. I wonder if the exchange right granted to her collectors lasts indefinitely.

It is normal for Buddhists to tear down a dilapidated temple and rebuild it in the same place without losing sanctity. Europeans tick differently, they like it rather old, because only what is old, is good, is real and what is genuine, is expensive to them - and so here is the collector in a predicament.

Patrick Huber

Delays arranged- Bettina Buck invites Jo[...]

PDF-Dokument [26.5 MB]

DelaysArranged_05_Ansicht (1).pdf

PDF-Dokument [1.5 MB]