Bernshammar, November 8, 2023

Dear Simon,

It is four years since we first talked and you introduced me to your

works. As I wrote earlier, your paintingsbecame windows onto my own past. Your home village, Ottersberg, transformed into Kolsva, the Swedishvillage where I grew up. Everything seemed so familiar to

me: from the dirty plastic furniture in the gardensto the melancholic atmosphere, and the tensions between beauty and ugliness.

Yesterday, I told you that my wife, dog, and I moved to a house in

the countryside a few years ago, 10kilometers north of my childhood village. It is an area of vast forest lands, lakes and rivers, affected bycenturies of iron handling; mines, smithies and

ironworks. The industry is gone, but its traces are visible. Ialso think that it has shaped people’s views of nature as a resource to be exploited.

Several of the old forests that were here when we moved in are gone.

If you are unlucky, your immediatesurrounding may be devasted in the course of a few weeks, and there is nothing you can do when theforest machines are approaching. Economic growth and job

opportunities beat everything: ecology andbiodiversity as well as beauty and well-being. This is true everywhere, but it is especially pertinent to thecountryside. Why? Because rural ugliness is more

large-scale and radical than urban ugliness. Cityugliness tends to disappear into the background of everything that goes on. Rural ugliness doesn’t. A clear-cut forest is a wound. It absorbs

everything that is beautiful around it.

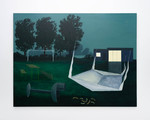

There is an increased distance in your new paintings, between the

viewer and what is seen or recollected.To me it seems that there is a shift in focus from the place as such, to the relation between place and aviewer. I wonder who the viewer is. Someone who walks

by, and stops for a while to have a look, orsomeone who belongs there? What does it mean to belong? To be part of something, a community, aplace, a ”we”. To not be

alone.

The distance between the viewer and the houses, pools, and things in

your paintings makes the viewerseem lonely. It is someone who doesn’t participate. The loneliness is emphasized by the absence ofpeople. We talked a lot about loneliness yesterday. You told me that

you spend most of your time inHamburg in your studio, and that you don’t often spend time with other people in the city, with the exceptionof your little son. Without your loneliness, you said, your

paintings would not have become what they are.Your social life instead takes place in your home village, when you go there to visit your family and friends.

I share your view on loneliness as something precious. But in

contrast to you, I want my life in thecountryside to be as lonely as possible: to work, think, read, walk, and occasionally to build something. Tobe honest, this kind of loneliness isn’t really very

lonely. Hannah Arendt referred to it as solitude: ”In mysolitude I am by myself, together with myself, and therefore two in one, whereas in loneliness I am actuallyone, deserted by all

others.”

I returned to Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism last

week, with the hope of becoming lessmiserable and confused about what’s going on today. It helped. Her thoughts on solitude and loneliness arebrilliant. In the dialogue with ourselves, that takes

place in solitude, we never lose touch with our fellow-humans; they are present in the self that we speak with. Loneliness, on the other hand, is a curse. To belonely is to be superfluous, to be

deserted not only by other people, but also by one’s own self. The realdanger is that it makes us receptive to totalitarian diseases. I believe her.

My best,

Jens

Letter from Jens Soneryd to Simon Modersohn, Kleines Gedeck.

November 11–December 9, 2023. Åplus, Berlin.