Ceci n‘est pas une pipe.

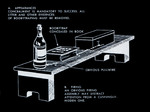

The images here are based on two books, published by the US military in the 60s. In these books, soldiers were trained on how to construct boobytraps – i.e. explosive devices that disguise themselves as everyday objects. The pipe shown here, only on the outside, claims to be a pipe. It isn’t one though.

The idea behind this, and something that is explained in these books, is to instill fear and uncertainty in your opponent. Your opponent ought to lose trust in his or her surrounding environment. And once that is achieved, it becomes paralyzing. While it is possible to find a certain boobytrap in a room, proving the negative is nigh on impossible. That means that you can always only find positive evidence for the existence of something, never for the absence of something. Looking at boobytraps as an example, if the pipe isn’t boobytrapped, every other thing might be. There is always room for the feeling of terror.

How to Pickpocket

These images are based on instructional material, created by the communist era Czechoslovak secret police STB. Given the track record of authoritarian regimes and the security apparatuses all throughout history, this material has to be read in two directions. Yes, it could be an

instruction on how to spot and catch pickpockets, but it definitely works as an instruction on how to pickpocket as well. Somehow, the latter feels even more plausible to me.

Tourism and War and the Problem of the Archive as an Institution

During the Second World War, right after Germany had invaded France, the British BBC Told their audience that they were planning an exhibition on the lost landscapes of Europe. Audience members were asked to send vacation photographs and postcards, depicting the landscapes and places of Western Europe that were now inaccessible to Brits. This story was a lie. In fact, the British high command had realized that they were lacking crucial information on the geography and architecture of the countries across the channel, if they would ever try to free them from fascist rule.

This became a massive crowd sourcing endeavor for information – long before crowd sourcing became a thing. Roughly eight million images were sent in and 800.000 of those were reproduced and organized. It could be a tale about the fact that innocent looking material can easily be used for other purposes and in the times of Facebook and co. this could be quite relevant. But it has become a tale about the issue of archives and ownership. The material discussed here does still exist, even though almost no one knows about it. I was able to look at some of the material by opening boxes that had been tied shut after the end of WW2. But the archive did not want me to use the material. Why? Difficult to say, since I was never really given a real explanation. Must have to do with money and power.

To me that raises the question of ownership. Archives ought to be the stewards of information, especially highly relevant such as this set of files. And not the gatekeepers who decide how certain moments in history have to be understood.

Simon Menner