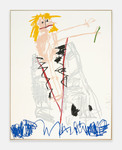

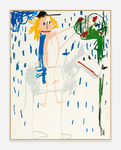

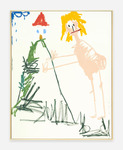

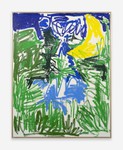

If in Andi Fischer's painting a knight goes into battle, confidently and vivaciously screams "TaTa Ongart", this is as feisty as it is touching and should still be taken seriously. The exclamation "TaTa Ongart" is also the title of the exhibition, which features three object boxes and eight new paintings from this year. By tossing overboard all rules of painting, by scribbling and scrawling, Andi Fischer brings to light a whole new layer from a medium that has engaged theorists and artists for decades.

Obviously, painting badly on purpose is not a new invention, as quite a few painters have done that before. Moreover, to think that Fischer would paint like a child is completely wrong, even impertinent, since not a single child in the world would ever paint like that.

The works do not represent naive scenes, but relate to hundreds of years of art history.

His way of doing is like of a decoder’s and his works are image-formed, rephrased transfers:

myths, struggles and existential concerns already found in the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens or Albrecht Dürer are here translated into the aesthetics of now.

It is not that people's existential needs and feelings have changed over the decades.

The circumstances may have changed, but not the great battles that a human being must fight whilst alive. Each single image unravels and interprets a human condition, providing a bit more clarity. At the same time, his painting stubbornly opposes a society that collectively strives for perfection and in which every flaw and defect is cast into a mold for perfection, fueling further the categories good/bad and beautiful/ugly.

Fischer's works skillfully evade these categories, because at first, one always wonders how to see through them. Thereby, they break the mold demonstrating that everything that shrinks under the pressure of perfection and a smooth façade is simply impossible.

The object cases from the other hand put on stage great stories with a few, simple touches.

They also question the concept of collecting in a museum, what is preserved and presented, and why?

At first glance the paintings and object cases seem funny, awkward and nonchalant. But once decrypted, one realizes that they actually are quite simple. That they tell about love, pain, death and transience. That in them lives a drama which is not afraid of pathos. That the placed pathos is embraced here and is essential for understanding what drives people. And this essence is possibly what makes good art.

Yet, Fischer's paintings are apparently a bit like writing about them: The more complicated one expresses oneself, the higher the probability that one hasn't understood it properly. And if one looks at it that way, then one can assume that Fischer has understood his thing very well.

Laura Helena Wurth

Translation: Majla Zeneli

Wenn bei Andi Fischer der Ritter in die Schlacht zieht und voller Zuversicht und Tatendrang “Ta Ta Ongart” schreit, dann ist das genauso rührend wie angriffslustig und sollte dennoch ernst genommen werden. Der Ausruf ist der Titel der Ausstellung, die drei Schaukästen und acht neue Malereien aus diesem Jahr zeigt. Indem Andi Fischer in seiner Malerei alle Regeln über Bord wirft und krickelt und krakelt, entlockt er dem Medium, das die Theoretiker - und KünstlerInnen seit Jahrzehnten beschäftigt, eine ganz neue Ebene.

Mit Absicht schlecht zu malen, ist natürlich keine neue Erfindung. Das haben schon etliche vor ihm getan. Und auch zu denken, er würde wie ein Kind malen, ist gänzlich falsch und sogar vermessen. Denn kein einziges Kind auf der Welt würde je so malen.

Die Bilder zeigen keine naiven Szenen, sondern beziehen sich auf Jahrhunderte der Kunstgeschichte. Seine eigentliche Leistung ist die eines Übersetzers und seine Arbeiten sind Bild-gewordene Transferleistungen: Die Mythen, Kämpfe und existenziellen Sorgen, die man schon in den Gemälden von Peter Paul Rubens oder Albrecht Dürer finden konnte, sind hier in die Ästhetik des Jetzt übersetzt. Es ist ja nicht so als hätten sich die existenziellen Bedürfnisse und Gefühle der Menschen über die Jahrzehnte verändert. Die Umstände haben sich verändert, aber nicht die großen Kämpfe, die der Mensch unweigerlich ausfechten muss, wenn er am Leben ist. Jedes einzelne Bild entwirrt und decodiert einen menschlichen Aggregatzustand und schafft ein wenig mehr Klarheit. Gleichzeitig stellt die Malerei sich trotzig einer Gesellschaft entgegen, die kollektiv um Perfektion ringt und in der jeder Makel und jede Schwäche wieder in eine Form von Perfektion gegossen wird und damit die Kategorien gut / schlecht und schön / hässlich nur noch weiter befeuert. Fischers Arbeiten entziehen sich diesen Kategorien geschickt, weil man im ersten Moment immer schon denkt sie zu durchdringen. Dabei sprengen sie den Rahmen und führen allem was sich dem Druck nach Perfektion und glatter Fassade beugt, die eigene Unmöglichkeit vor.

Auch die Schaukästen führen mit ein paar wenigen Handgriffen große Geschichten auf.

Der Schaukasten greift dabei, wenn man will, auch den Begriff des musealen Sammelns auf und lässt fragen, was man eigentlich sammelt, bewahrt und präsentiert. Und warum eigentlich?

So scheinen die Bilder und Schaukästen nur auf den ersten Blick witzig, ungelenk und nonchalant. Wenn man sie aufbricht, dann erkennt man, dass es eigentlich ganz einfach ist. Dass es um Liebe, Schmerz, Tod und Vergänglichkeit geht. Dass in den Bildern eine Dramatik wohnt, die keine Angst vor dem Pathos hat. Im Gegenteil, das Pathetische wird hier eingehegt, umarmt und ist wichtig, um zu verstehen, was den Menschen bewegt. Und dieser Bezug aufs Wesentliche ist vielleicht genau das, was gute Kunst ausmacht.

Außerdem ist es mit Fischers Bildern wohl ein wenig so wie mit dem Schreiben darüber:

Je komplizierter man sich ausdrückt, desto höher die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass man es nicht richtig verstanden hat. Und wenn man es so betrachtet, dann kann man davon ausgehen, dass Fischer seine Sache sehr gut verstanden hat.

Laura Helena Wurth

For Andi Fischer

THINGS TO REMEMBER. REVISED AND EXPANDED LIST.

1. We are shivering, trembling and fearful beings.

2. Read the Swedish philosopher and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, to learn more about the importance of trembling and small motions.

3. Each style is the result of a particular way of trembling. Make sure that your paintings, drawings and wood works continue to tremble in their unique, dynamic and forthright manner.

4. It is a well-known fact that intense fear makes us tremble. You said that fear connects us with the history and the lives of people in the distant past. One of the reasons that we still can understand the old masters is that we share the same fears.

5. We have always been afraid.

6. We have always tried to overcome our fears.

7. Why do we try so hard to defeat our fears? One answer is that ever since the Bible we've constantly been told that fears are irrational and useless. This message made sense earlier because of God’s omnipotence and goodness. But in a world without God, it makes no sense at all. It's obvious that science, reason, technology and the other things we've invented to replace God with don’t have the power to annihilate fear.

8. We tremble with fear because we care. Under the influence of nihilism, I once did a serious attempt to rid myself of fears because I thought that it would be easier for me to do what I wanted without them. It didn't end up well, not well at all. Only a world devoid of meaning is a place where fear is superfluous.

9. Use your fears as scouts, a wise woman recently said to me, and I try to follow her advice. You told me that you keep your fears in a box and that you sometimes let them out. That is also an appropriate way to handle them.

10. It is ok to make works that are both funny and dreadful – even during a pandemic and a climate crisis. My guess is that Hieronymus Bosch alternately laughed and trembled with fear when he worked on the hell section of The Garden of Earthly Delights, and I wouldn't be surprised if Peter Paul Rubens did so too, when he painted Prometheus Bound.

11. Albrecht Dürer was also an impressive trembler.

12. Luck is luck. Don't downgrade your luck by calling it a skill, hard work or something else it isn't.

13. A nose is a nose. But it may also be a cross or something else. You never know.

14. Art works know more than their makers. Fears sometimes know more than those who experience them. Hands always know more than the persons they belong to.

15. Treat your hands and fears like dogs: allow them to move around unleashed at least a couple of hours every day.

16. To make art is not to work. Work is easy to define (you perform certain tasks that someone pays you to do and then you become alienated). Art is not.

17. If you're lucky, you might make a living from art. But that doesn't mean that it's work. It's just luck.

18. It feels good to be lucky. It also feels good to do things that are easy to define. To be fearful doesn't feel good, but it is good anyway.

19. Don't pretend to be abnormal in a way that you are not just because it happens to be fashionable. Develop your own abnormality instead, your own specific way to shiver and tremble.

20. Meaning is not use. It's not function. Meaning is trembling.

21. I like your new works a lot. I think I like the wood works simply because I like trees and enjoy wood carving myself. Your landscape paintings are very different from all other landscape paintings I've seen. They don't tell how a landscape looks, but how it feels to be there. They have no vantage point. It is as if they were made before linear perspective was invented.

22. Stay fearful, be lucky and keep trembling.

---

Jens Soneryd

Bernshammar, Sweden, April 2021

Å+ Andi Fischer - TaTa ongart.pdf

PDF-Dokument [32.7 MB]