Jakob Argauer, Bernhard Buff, Billie Clarken, Andi Fischer, Lars Fischer, Max Frisinger, Hannah Hallermann, Lauren Keeley, Felix Kultau, Line Lyhne, Lulu MacDonald, Ellen Möckel, Simon Modersohn, Philip Newcombe, Robert Schwark, Sophie Schweighart, Adrian Williams

2 Zimmer, Küche, Bad

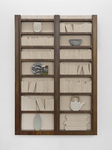

Lulu MacDonald

2 Zimmer, Küche, Bad describes a German flat. In England, we describe houses or flats by how many bedrooms they have, not simply by the number of rooms. What do we need from our flat? A space to sleep and a guest room? A home office? Will we have a child one day?

In England the living room is a given: it’s a space to commune, to come together. In German, by describing each space just as a room and not defining its purpose from the get go, I stumble occasionally. Could flats and other living spaces begin to be more flexible? Or is it just another typical moment in the German language where one mustn’t assume or dictate how to be, how to live. Back in the day as an art student in London, six of us lived in a five-bedroom house on Fairbridge Road. My best friend Sophie slept in the “living Room” and by her use of our living room we made the house affordable—we made it so that we could all sleep there. I know of families who have turned their living rooms into hybrid spaces where the parents sleep at night and then turn them back into spaces to live in during the day. Then there are the couples who prefer to have separate rooms, so one takes the living room and the other sleeps in the bedroom. My neighbors use an entire small bedroom (or a half-room in German) as a prayer room. There are many other differences between flat rentals in England and in Germany, and one of the most obvious is moving into a new flat and not having a kitchen. This refers to the appliances, sink and cabinets, not the space itself. As if moving flats wasn’t annoying enough, you now have to find/buy/steal everything for the kitchen, install it or build one yourself, or bring it all from your last flat with you—assuming your friends like you enough to help carry it up the stairs.

The main similarity is, of course, that flats in both places are too expensive.

Flats or safe spaces to sleep are a fundamental need. Any of us could end up becoming homeless or having to sleep rough. Yet when we go home, it’s the furthest thing from our minds. When we scroll

through the flat offers and are appalled by the prices, a feeling of outrage rises instead of one of deep circumstantial privilege. My home or your home is a safe space, a place of the utmost

intimacy: we eat there, we drink there, we can make love in any of our rooms, we talk, we laugh, we think, we make plans, we build memories.

Making art or creating objects is often an attempt to remove the constructs of formulaic compartments that are thrust upon us. We artists, however, are all making work that pulls apart the confines

or constructs only to end up being hung on the wall in your living room. An object to live with—what does it mean when the work I made on the dining table in my living room ends up displayed in your

living room? The art object or picture becomes a part of your decoration, your interior design. I am invited into your space, and become part of it.

The exhibition “2 Zimmer, Bad, Küche” invites both the artists and the observers to imagine and reimagine one's walls. “Zu Hause” or “Home” might trigger domestic, toxic pasts that you prefer to

forget. But these terms also conjure the potential that your flat offers to be reminded not only of how rigid and sturdy those walls are, how anchored your feel, how settled you are, but also of how

elastic, how flexible and how absolutely you aren’t confined to just “2 Zimmern ein Bad und nur eine Küche”.

Get home safe.